Every writer has that story, or moment, that’s stuck with them and inspired them so much they’ve wanted to incorporate it into their own work. Whether it’s the magic of Dorothy opening the door of her sepia home to see the Technicolor land of Oz, the chilling moment Muldoon realizes Jurassic Park’s raptors are truly clever girls, or the thrills the Orient Express fight from James Bond’s From Russia with Love everyone has that moment. All of these movies were adapted from another medium entirely. In this case, all began their lives as novels. This might sound like something that only affects straight adaptations of existing works, but it’s something that affects many creators. What if your inspiration comes from a different medium entirely? How do you use that?

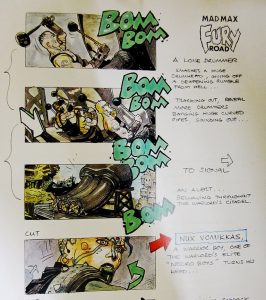

Movies have been adapted from books since the advent of the medium, and books create novelizations of movies or games and at times try to expand a universe they established. Mad Max: Fury Road had a script that could be compared to a comic. Video games are trying to capture the cinematic experience of the movies, and movies are trying to adapt interactive video games. While this had worked magic in the case of Mad Max and others, the practice so often falls flat. If you’ve ever gone to a movie with a friend who’s read the original novel, you’ve been informed many times over, “The book is better.”

Your friend’s often right, not because movies aren’t capable of making the jump, but because the movie being made didn’t really take inspiration from the source. It either threw everything out the window and became an In Name Only adaptation, or it simply hit the plot points the book follows. Neither one of these turn out well because they miss the most important part of the equation: the spirit of the original. And this is the same kind of lesson you should take to heart when you’re looking at inspirations that you want to incorporate into your own work.

When trying to incorporate something that inspired you into another medium, the most important thing to realize is that, more often than not, you won’t be able to recreate the moment that inspired you exactly as it is. You wouldn’t want to, even if you could. The goal should always be to do more than just file off the serial numbers. What you want to capture is the essence of the thing.

First, you need to analyze what inspired you and figure out what it is exactly you wanted to adapt for your own work. Once you’ve figured out what aspects inspired you, consider them separately from the rest of the work. How you can use those elements? Instead of trying to write out the exact sequence of events of The Italian Job’s mini cooper car chase, a scene built from the ground up to be watched and not read, consider how your own medium can capture the thrill of that chase while also sticking to the cleverness that is essential to the heist genre. In doing this you’ll often find that your work is already well on its way to having a voice of its own, while still holding to the spirit of your inspiration.

One of the best examples of jumping mediums is The Princess Bride. The original novel was written by William Goldman and published in 1973. It is a fairy tale built around the idea that Goldman is providing an abbreviated version of a much longer and much more boring book that his father used to read to him as a boy. Upon reading it himself as an adult, he realized his father had taken out all the lengthy political commentary. His father had only read him “the good stuff,” and his own abridged version is an attempt to recapture the magic of what his father read him. A great deal of the humor is in the footnotes that have been added – providing author commentary and summary on what was removed from the original.

When Goldman adapted his novel for the big screen the footnotes had to go. In their place we got something more suited to the medium: narration. The film takes what the novel used to set up the premise of the abbreviated novel – a father reading his son a fairy tale – and made that the framework of the film. Now it’s a grandfather reading to his sick grandson. This lends itself beautifully to the shorter run time (and with it, the faster pacing) of film. The commentary runs over the scene, capturing the spirit and humor of the novel.

Let’s focus on a comparison of the opening scene and the opening chapter of both versions. It’s immediately clear how well Goldman adapted The Princess Bride. The book (and you can read the opening excerpt here) begins with some backstory for Buttercup and a running joke about each of the most beautiful women in the world up until that point – and how they ultimately lost the title. This takes advantage of the medium’s ability to meander, setting the tone for the whole story. The novel takes time to set up the world in which the story takes place, before the characters are properly introduced.

The movie, however, starts by introducing characters, the sick grandson and his grandpa.

In a couple of minutes the scene sets up the conflict of a generational gap. The opening image is the kid’s video game. Soon, his grandfather walks in with a gift – a book. On one side the grandfather feels out of touch with what his grandson likes, on the other the grandfather is determined to bring the kid into the family’s grand tradition. This isn’t just any book. This is the book his father read to him when he was sick, and then when his son was sick he read the book to him, and now he’s determined to read the book to his grandson. It takes advantage of the visual medium, using the actor’s delivery and the camera’s focus to supplement the dialogue, getting these points across in two minutes flat.

When the grandfather does start reading the story, we begin at the last two paragraphs of the novel’s first chapter, focusing on Buttercup and Wesley’s relationship over the backstory that the novel has time to deliver. The kid’s comments and the grandfather’s narration continue, giving the movie the same tone and style of the book, while the actors, music, and cinematography all allow for the audience to get information that the book needs more time to describe. The kid’s impatience cuts into the story, and the grandfather skipping or speeding through bits of narration keep that same idea the book was built around: we are seeing just “the good stuff” from a much longer – and much more boring – fairy tale.

There’s a lot more we can learn about adapting our inspirations by looking at more literal adaptations such as The Princess Bride, and even the ones I only mentioned in passing such as The Wizard of Oz, James Bond, and Jurassic Park. They all prove that it’s not only possible to take inspiration from from a different medium, it’s that kind of cross-pollination that can lead to something great. Or something classic. Walt Disney’s animated films were inspired by stage musicals, incorporating the aspects he loved into his own, new medium. Soon the inspiration went with both ways, and his films inspired stage musicals in their own way. Take inspiration from wherever you can find it, and always be mindful of how that inspiration can be strengthened in your medium of choice.

Nicole Petit writes because no other job lets her sleep until noon. She curated the collections Silver Screen Sleuths (#1 Best Other Short Story—Critters Readers’ Poll), Speakeasies and Spiritualists (Best Magical Realism Short Story; Best Other Short Story; as well as top ten Best Horror stories & Best Anthology—Preditors and Editors Readers’ Poll 2017), After Avalon (#4 Best Anthology—Preditors and Editors Readers’ Poll 2016), and From the Dragon Lord’s Library (Best Story and Best Cover—PulpArk New Pulp Awards 2016). The Preditors and Editors Readers’ Poll named her #1 Best Editor overall. Her latest book, Sockhops & Seances, is available now!