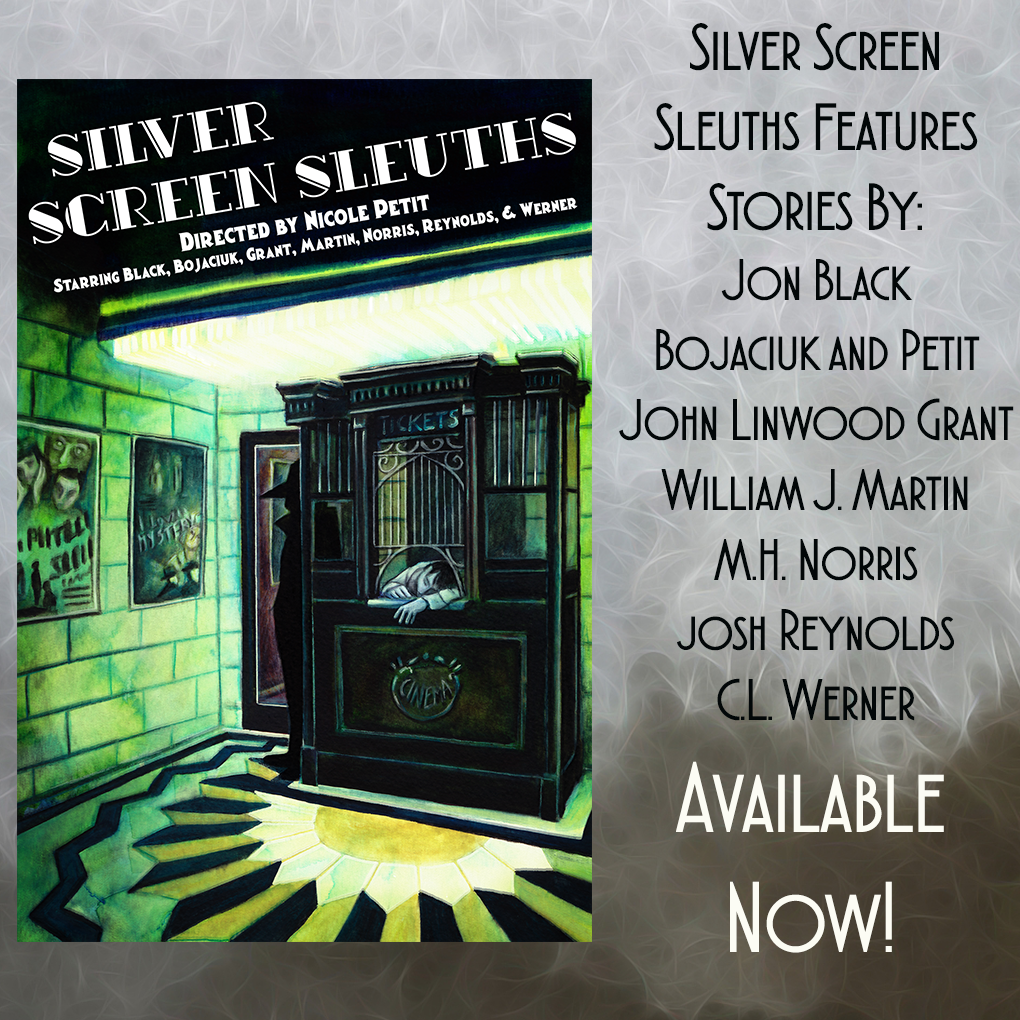

Josh Reynolds’ “Green Hell, Red Murder” (from Silver Screen Sleuths!)

We’re pleased to present our first excerpt from Silver Screen Sleuths, an exclusive look at Josh Reynolds’ story.

EBOOK

18THWALL | AMAZON US | AMAZON UK

A paranoid director tasks Vincent Price with discovering why a dead man was found in his temple set.

It was the worst heat wave the City of Angels had experienced in almost forty years. The forty odd thousand square foot confines of the interior jungle set for James Whale’s latest picture were almost as sweltering as the real thing. The stage hands were in a war of attrition with the humidity, and production assistants were waving clipboards like fans, trying to keep the cast from melting. There were rumours that Fairbanks had collapsed from heat stroke, and that George Bancroft was running amok somewhere.

All in all, I was quite happy to be dead, and lounging in the shade.

“About five of the worst pictures ever made are crammed into this one,” I said. I was on my third cigarette of the morning. I held out the pack to Ray, who took one.

“The doctors say these will kill me,” he said, before lighting up. “And that’s being a bit harsh, Vincent. We’ve both been in worse films.” He gave me a flat smile. “And will be for many years to come, if the fates are kind.”

“Speak for yourself,” I said. “I suspect I’ve reached the apex of my cinematic journey. Two poisoned arrows to the chest and a bit of melodramatic writhing.” I tapped my chest for emphasis. “Hardly a praiseworthy career.” It was a bit part, but I got last billing. It’s said that last billing is better than no billing, but I was having a hard time seeing the upside, career-wise. Such is the lot of the bit-player.

“Four years ago, I shared top billing with a horse and a dog,” Ray said. “Now I’m playing a jungle savage, with fewer good lines than a character who got two poisoned arrows to the chest.” He quirked an eyebrow and blew smoke at me.

“Don’t forget the writhing. I am quite proud of the writhing.”

“Almost Shakespearean.”

“Well, I did get my start on the stage.”

Ray laughed. There was nothing quite like watching Ray Mala laugh. His face, usually about as expressive as a chunk of teak, broke into canyons and crinkles. He clapped me on the shoulder, coughing slightly.

“That’s why I like you, Vincent. You make me laugh.”

“My talents are many and varied, Ray.” I puffed on my cigarette and studied the interior of the subterranean Incan temple that had led to my most recent death. The studio had spared no expense on it—it rose wild, a blossom of heathen idolatry, crammed into a sound stage. It was the dais that drew the eye—a slab of faux-stone, surmounted by an immense menhir, ringed by a quartet of stylised, vaguely capric statues. Deer or goats or antelope, they didn’t quite fit the theme. None of it did, really, despite the profuse amounts of plastic and paper flora clumped and scattered over the set in haphazard fashion.

Even so, it was a masterpiece far out of proportion with its current display. Cyclopean and intimidating, with an air of primitive mastery to it, it hinted at far better stories than the one currently playing out within it. I had no doubt Universal would use the set again, whenever they had need of something suitably exotic. Trade out the vines for sand, and it’d be a perfect Temple of the Seven Jackals or what have you.

“I heard Douglas tried to swing on one of the vines,” Ray said. “Came off in his hand and dumped him on his ass.”

“Serves him right. This isn’t Zenda, and those aren’t chandeliers.”

“Did he swing on any chandeliers in that one?”

I blew a plume of smoke. “Not during the film.”

Ray smiled. “You’re just annoyed because he ran off with your wife.”

I choked as smoke went down the wrong pipe. As I bent over, wheezing, Ray patted my back sympathetically. I knew he’d meant Joan Bennet, who played my late character’s wife. My part was so miniscule that I hadn’t had a chance to meet her before I was out, she was in, and the jungle was a-swelter with illicit romance between her character and Fairbanks’ dashing adventurer. But for a moment—just an instant—I’d been thinking of Edi. My Edith.

Not unusual, all things considered. We’d been having some difficulties, of late. Broadway wasn’t being kind to her, and none of the usual comforting pabulums were doing the trick. My successes, meagre though they were, weren’t helping matters. Nor was the distance—she was still on the East Coast, while Hollywood had caught me up in its sun-drenched claws. I’d suggested we split the difference and move to Kansas, but she hadn’t appreciated my attempt at humour. Edi was a tougher audience than Ray.

I forgot about Edi when the first scream echoed over the lot. Ray and I looked at one another. Then, a second scream followed the first, rising up like the wail of a fire engine. It was coming from the temple. We started forward, along with everyone else with two legs and a pair of ears. There was a stampede towards the looming eidolon, with its fake greenery and grisly decorations. One of the native girls—really, a former waitress from Long Island—stumbled into the open, eyes wide. She screamed again, showing off a set of lungs that would have made Weissmuller jealous.

Members of the crew were already crawling over the artificial edifice, seeking whatever it was that had set her to sounding the alarm. As we arrived, they found it.

Him, rather.

To the surprise of no one, shooting was cancelled for the rest of the day.

The next morning, I found myself in the scrap of a lot office that James Whale had claimed for his own. It was early enough that the drunks were singing in accompaniment with the birds on Cahuenga Boulevard, but the Universal backlot was silent. No scratch of tools or shouting teamsters. It was unnerving, I admit. You get used to the noise—the constant pressure of a hundred voices, all speaking at cross-purposes. It’s only when it goes silent that you realise just how big and empty a sound stage truly is. An infinity of possibilities.

Whale looked like a man who’d been subsisting entirely on coffee and cigarettes for too long. He was still handsome, in that brittle British way, but you could see the cracks in the facade. The rumour was, he was on his way out. A shame, but then, I wasn’t even in, so who was I to commiserate? Whale had been a name, once. A director on the rise.

But then the Laemmles had lost control in ’36, when the studio went bankrupt. Showboat had sunk them, for all that it had been a success. And with the Carl and Junior out, Whale’s rising star had turned into a falling one. I’d heard about the mess with the Germans and The Road Back—everyone in town had. Whale had won the battle, but lost the war. Rogers, the new studio head, was trying to figure out a way to get rid of him without breaking their contract, but Whale wasn’t having any of it.

Thus, the great man had found himself directing a string of B-movies, including the currently in-production Green Hell. Whale was beaten down, with a hangdog look on his long, English features. Nonetheless, he eyed me keenly. “You made for an engaging Albert, when I saw you on stage a few years ago.”

“It wasn’t difficult. He was a charming man.” I had played Prince Albert in the American production of Houseman’s Victoria Regina. Not one of my more well-known roles, but one I was proud of, nonetheless.

Whale smiled. “Have you ever given thought to a more hardboiled part?”

“I’m open to opportunity,” I said, trying to hide my eagerness. Was I being offered a part, in another film? My last starring role had involved being invisible for the majority of my screen-time. I don’t recommend it.

The door closed behind me. I turned, and saw the familiar figure of the studio fixer, Earl Hoskins, looming in front of it. Imagine a chunk of granite, chopped carelessly, and stuffed into an expensive suit in an effort to hide the flaws in its shaping. That was Hoskins. Officially, he was just another studio executive. In reality, his purpose was more colorful than corporate. Hoskins was a new breed of middle man, designed and built by the studio system to make sure scandals stayed quiet, and that all the moving parts performed their function without interruption. “You ask him yet?”

“I was getting to it.”

“Hurry up. I can’t keep the cops off of the set forever.”

“Then don’t.”

“This film is already over-budget and behind schedule.” Hoskins spat the Four Deadly Words like bullets. Whale twitched but didn’t otherwise react. I shrank slightly in my seat, trying to inch out of the line of fire.

Whale glanced at me. “You were on set yesterday? When they found it?”

“Yes. Poor Harold.” I reached for the pack of cigarettes in my pocket. The body they’d found had been that of Harold Gummer. A security guard, and something of a fixture on the backlot. Elderly, even by the standards of Universal security guards. I hadn’t known him well, but he’d seemed pleasant enough the few times we’d chatted. “Heart attack?”

“Arrows.”

I stopped, the pack half out of my pocket. “Arrows?”

“Poison arrows. Just like the ones that did you in.”

“But those are just props, surely?”

“Not when you break one in half and slide it between a guy’s ribs,” Hoskins grunted. He leaned against the door, arms crossed. “Better than a jailhouse shiv.” The voice of experience, I assumed.

“The props department will be pleased to hear it.” Whale looked at me. “It was murder. He was killed sometime the night before. The body was hidden.”

I lit my cigarette. Given the heat, I was surprised someone hadn’t stumbled over the body sooner, but I kept that little bon mot to myself. “Then why keep the police off the set?”

Hoskins set a heavy hand on my shoulder. “I thought you said he was smart?”

I glanced up at him. “This is about money?”

Hoskins grinned, despite my withering tone. “Look at that. He already found a clue.”

Whale sighed. “The police will shut down the set. We’re behind schedule already. But, if we can wrap things up nicely for them, before they start poking around, they might be inclined to accept our gift horse without first checking its teeth.”

I sat back. “I’m starting to see where this is going. But why am I here?” I tensed. “Am I a suspect?”

“No. You’ll be playing the detective.” Whale tried to smile encouragingly. He didn’t quite manage it.

“Why me?”

“You got a reason to be on set, even if you aren’t doing anything. We hire a private dick, word gets out, the schedule goes to hell.” Hoskins spoke flatly, grudging every word. He cracked his knuckles repeatedly, as if longing to thump someone.

“I know you’re at loose ends, Vincent. I also know you’re a good deal smarter than you pretend to be. You were an art procurer, for a brief time.”

“Still am, in the slow months.” When it came to buying art, it always helped to have a second pair of eyes. I was only too happy to provide those eyes, for a modest fee. Enough to cover the cost of a piece or two for my own collection.

“You have to have a good eye for forgeries in that line. The ability to see what a layman might miss. The little details.”

I sat back, digesting this. As parts went, it wasn’t the kind I’d had in mind. But, at the same time, I wasn’t doing anything at the moment, being in something of a professional dry spell. And house rentals in the valley weren’t cheap, on a bit player’s income. Besides which, I’d liked Harold. No one ought to die on a film set. Not for real, anyway. I looked at Whale.

“I’ve always wanted to don the deerstalker. How much does it pay?”

“We’re over budget,” Hoskins growled.

“It will be worse, if the police get involved,” Whale said, pointedly. He looked at me. “We’ll bump your salary. You’ll get what the leads are getting, in cash. Off the books.” Behind me, Hoskins made a choking sound. Whale ignored him. “Does that sound fair?”

“More than adequate,” I said. “I assume I am to begin by digging for suspects, among the cast and crew.”

“I already know who did it,” Whale said, bluntly. “I just need you to find them.”

I stubbed out my cigarette in the ashtray on the table. “And who are they?”

“The Nazis,” Whale said.

“It’s not the Krauts,” Hoskins said.

“I didn’t say it was the Krauts,” Whale said. “We’ve got plenty of goose-stepping pricks here. Can’t throw a rock in Illinois without hitting a Nazi.” He leaned towards me, the shadows turning his face into a Greek tragedy mask. “Mark my words, Vincent—it’s the Nazis. They hate my work. The only thing worse than a fascist is a critic.”

“And the only thing worse than that is a critic who’s a fascist,” I said. Hoskins gave me the side-eye, and I quickly sheathed my rapier-like wit. I recovered quickly. “Why do you think it’s the Nazis?”

“They’ve had it out for me since The Road Back premiered. You heard about it?”

“Who hasn’t?” Whale’s sequel to All Quiet on the Western Front had ruffled some feathers, including those of George Gyssling, the Los Angeles consul for the current German government. He’d squawked that the film had been unfair in its representation of the German people. Threats had followed, and the whole thing became one of those messes someone will inevitably write a book about, in a decade or two. “And you think they killed a security guard in order to shut down production?”

“I think there’s nothing they wouldn’t stoop to.”

I leaned back, already in need of another cigarette. Instead, I nodded. Never argue with a director. A glance at Hoskins told me he felt the same. Whale’s theory was unlikely, if only because he was no longer important enough to sabotage. At least not by the German government. But it was best to keep that to myself. I pushed myself to my feet.

“Even so, best to be thorough. I’ll begin with the young woman who found the body, and go from there.”

“You got a day, Price. That’s all the budget allows for,” Hoskins growled. “And I’ll be watching to make sure you earn every penny.”

“I feel more productive already. If you gentlemen will excuse me?”

As I left, another argument began. Or perhaps it was the same one. Directors and producers were uneasy allies in the eternal war against rival studios, and Whale was harder to clamp down on than most.

Days like this, I was glad to be a humble thespian.