If Walls Could Talk: This Day In History -The Story Behind The Miranda Rights

I remember when I first heard the story behind the Miranda rights. I was reading Police Procedure and Investigation: A Guide For Writers by Lee Lofland (which, if you’re writing anything that involves police and procedure I highly recommend this resource), and he spends a few pages discussing the Miranda rights since they are used so often on television shows and movies.

Why am I talking about this today?

I’m one of those history nerds that gets History.com’s “This Day In History” emails in my inbox every morning. This week, I scrapped my plan for my column when I woke up this morning and saw what was the lead story in the email.

On this day in History, the United States Supreme Court handed down its decision regarding the case, Miranda V. Arizona. This led to what is known as the Miranda Rights or the Miranda Warning.

That being said, did you know that Miranda was a real person?

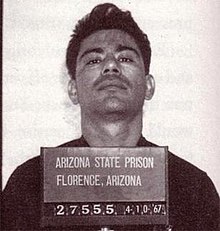

The origins of the Miranda rights go back to March 1963 when a 18-year-old Phoenix woman came to the police and said she’d been abducted, taken out to the desert and raped. Through a series of events, the police’s investigation led them to one Ernesto Miranda who already had a criminal history as a Peeping Tom.

What happened next is not commonly known. What is known is that after taking him into custody and interrogating him, Miranda gave a confession that was later recanted. No one had told Miranda about his Fifth Amendment rights.

Let me share with you the Fifth Amendment.

“No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.”

When it comes down to it, this amendment protects people against self-incrimination. In the case of Miranda V. Arizona, no one told Miranda that he didn’t have to talk.

Miranda was tried, found guilty (let’s be honest, part of this was due to the fact that his barely-paid defense attorney basically did nothing during the trial). The ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union) took on his appeal and managed to get his conviction overturned. The case made it all the way to the Supreme Court where the infamous decision was made.

Arizona retried Miranda without the confession and found him guilty again. After his release, he was later killed in a bar.

In a touch of irony, his killer chose to remain silent, using the rights given to him by Miranda V. Arizona.

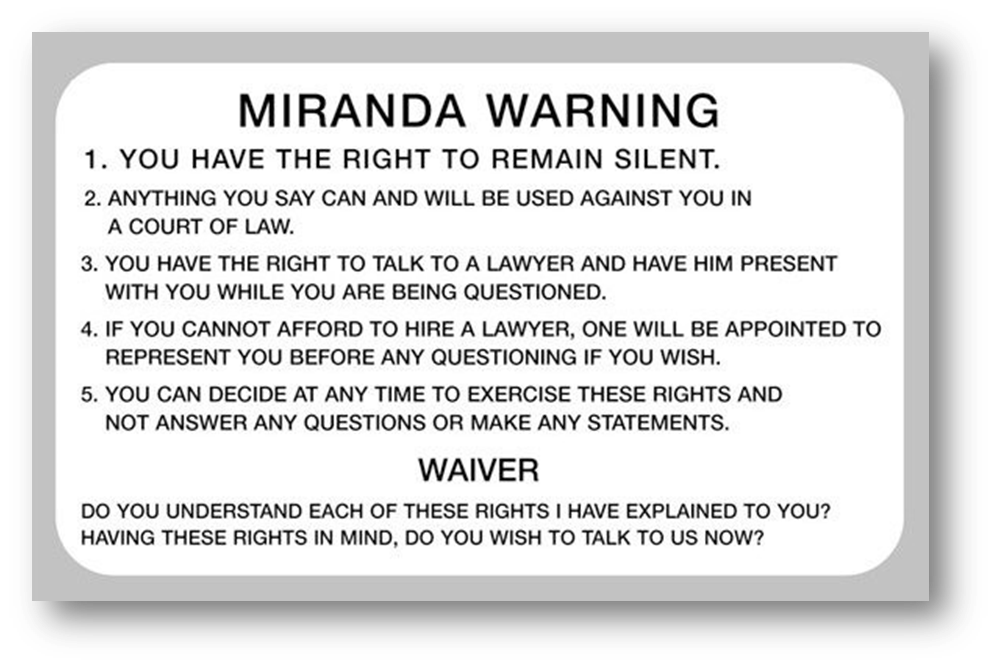

Everyone knows the Miranda Rights as they are shown on screen, ““You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can, and will, be used against you in court of law. You have the right to an attorney. If you cannot afford one, one will be appointed to you.”

One common misconception is that these rights have to be told to someone the second the cuffs are slapped on a person. Lofland says that’s not true. They must be made aware of their rights before you interrogate them, though.

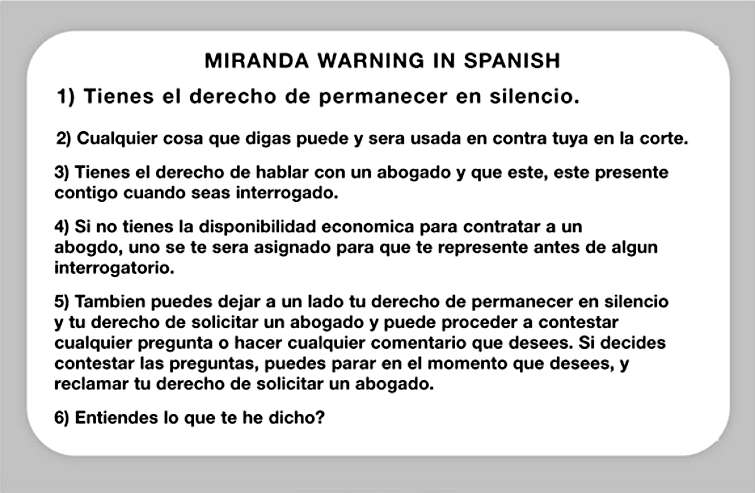

Often times, they will present cards with the rights written out and they will have the person sign saying they understand.

Another thing that’s notable about the Miranda Rights is that cases have been overturned because they aren’t given in a person’s native language. The most common language for this is Spanish, which is why cards in Spanish are popular. Some have English on one side and Spanish on another.

Let me give you a couple of examples where this has been done incorrectly.

I was watching Twin Peaks: The Return and there’s a scene where a principal’s fingerprints are found in a victim’s apartment and they bring him in for questioning. Before he even gets in the cop car, he asks for his lawyer, telling his wife to call him.

They take him to the station and again he asks for his lawyer and where he is. They said he’s coming and take him into an interrogation room and begin to question him.

No.

Just no.

The principal wasn’t dumb enough to fall for it and gave them nothing. Even if he’d said something, any lawyer worth the cost of their fees would have gotten it tossed out in court.

What made that scene worse was that they were so sure the principal was guilty that it seemed as if the officers were denying him his fifth amendment rights in favor of “justice.”

Let’s take a second to note. No matter if you’re 100% sure you have the right person (and they were not, the evidence they had was purely circumstantial) you cannot violate a suspect’s Fifth Amendment rights. If their lawyer doesn’t get the case thrown out on that technicality, someone like the ACLU will do it on the appeal.

On to my second example, Madea Goes To Jail. Near the beginning of the movie, Madea is caught on film on a high speed police chase. They catch her and her anger management issues ended up injuring several officers. She’s brought to court and her lawyer (and nephew) gets her out of it by pointing out that the officers never Mirandarized her.

THAT IS NOT HOW THEY MIRANDA RIGHTS WORK.

In this case, any statement Madea would have made would have had to be thrown out. But the case as a whole could still convict her.

Miranda rights only work against statements made by the defendant, not against the case as a whole.

The Miranda Rights are a little touch in your story, but doing them right can make you stand out.