The Chromatic Court: Simon Bucher-Jones’ “The Blues of the Endless Sky”

We’re pleased to present our next excerpt from The Chromatic Court – an exclusive look at Simon Bucher-Jones’ “The Blues of the Endless Sky.”

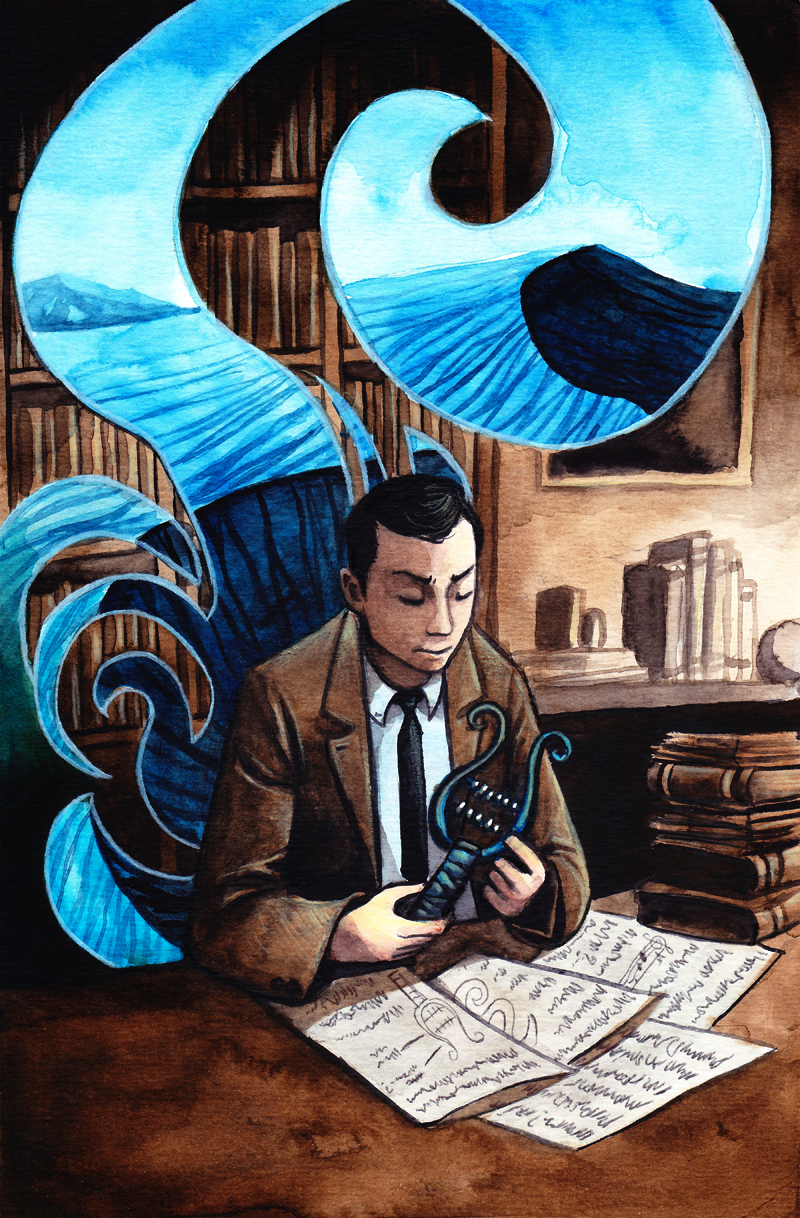

Featuring an exclusive look at Johannes’ Chazot’s illustration!

EBOOK

18THWALL | AMAZON US | AMAZON UK

“The introduction of novel fashions in music is a thing to beware of as endangering the whole fabric of society, whose most important conventions are unsettled by any revolutions in that quarter.”

Plato, The Republic (c.428 B.C. – c.347 B.C.)

Is music just an art or is it at the root of all arts? Music is after all mathematics made audible, as much an expression of ratios and proportions as anything in trigonometry.

It is, according to legend, Pythagoras to whom we owe the insight that first devised the Octave scale on which all Western music is based. In the seventeenth century, the mathematician Liebnitz corresponded with the musician Conrad Henfling about the application of Euclid’s work in the production of musical instruments and, in particular, in respect of their tuning to specific pitches. And, for a time, the classical world believed all was harmonious in nature above the moon, and so outward through the singing of the eternal spheres.

As early as Plato, writers were determined to limit and control music’s supposed effects upon the human psyche. What is art, but the recording in another mode of stimuli intended to influence the human mind?

So I once naively thought, until I learned songs humans never sang.

My field of study was, and is, musical history, in particular that aspect called comparative musicology—the study of the different types of tonalities and their historical variations. I was, and had been from my youth, obsessed with the idea that the very earliest music might be recreated, by analogy with, and by observation of, the varied musical traditions of the current world. For, it seemed to me, not every cultures’ music would have changed at the same rate, and here and there, a careful and sensitive ear might still detect the songs the sirens sang, or the drum–beats played by the earliest hunters to stir their blood to bring down the Mammoth or to drive the Smilodon from their caves.

In order to seek musical experiences from far and near, I pestered my fellow students throughout my time at university, and as we went our own ways in the wider world beyond its gates—I enjoined them to stay in touch with me and to advise me of any unusual or esoteric musical forms, whether old or new, which they might stumble across. As, I was relatively wealthy, at least at first—for the present stock market crash was then five years in the future—I was easily able to defray my friends’ expenses in writing to me, and to arrange for the wax cylinder recording of any novel works of musical art. For a time, I amassed a great library of music and a grand collection of recordings.

Thus it was that, until 1929, I felt as secure as a musical spider, whose web reached out into the world and vibrated with sounds as diverse as the valve-less trumpets of Denmark—recorded for me in a tiny village by no less a person than an assistant to the US Ambassador to Copenhagen—and the drums and percussive music of the American Indians.

Alas, in that year, my great work of musical rediscovery still only half written, I found myself required by the necessities of sudden poverty to seek work. Instead of being the patron who purchased obscure recordings from my many acquaintances, I was reduced to the penning of begging letters, asking whether or not I might add my scholastic abilities to one of their endeavours. I believed at first I would be a benefit, as I was an avid note taker, an enquiring mind, and a reasonable mathematical logician. I was, in those days, possessed of the quality termed ‘perfect pitch,’ and although I had lived a quiet scholastic life, I was not unfit physically. Despite these qualities, however, I soon discovered that poor young men were not, in 1929, a rising commodity, and I began to contemplate eventual starvation, as my remaining funds would gradually be spent no matter what economies I might make.

It was in this condition that I was glad to receive a letter from a particular favorite of mine among my correspondents. Paul Mennens had been in the anthropology department of the University where we had both studied, and we had often argued late into the night as to whether or not Neanderthal men had a voice (the evidence of both Francis Turville-Petre’s dig in Galille and Dorothy Garrod’s discoveries on Gibraltor being maddeningly incomplete in respect of the hyoid bone in the larynx)—I said yes, Paul said nay—or exactly what it was about the Mixolydian Mode that Plato feared would effeminise the men of Greece. Paul had told me some shocking secrets of Greek history, which suggested that Plato was wrong to fear the arising of what already seemed so common a practise. It was he who had told me the whispered legend of the Chromatic Court, the δικαστήριο των χρωμάτων said to predate the Grecian Muses from whom all the arts including music had filtered down into the primal psyche of mankind.