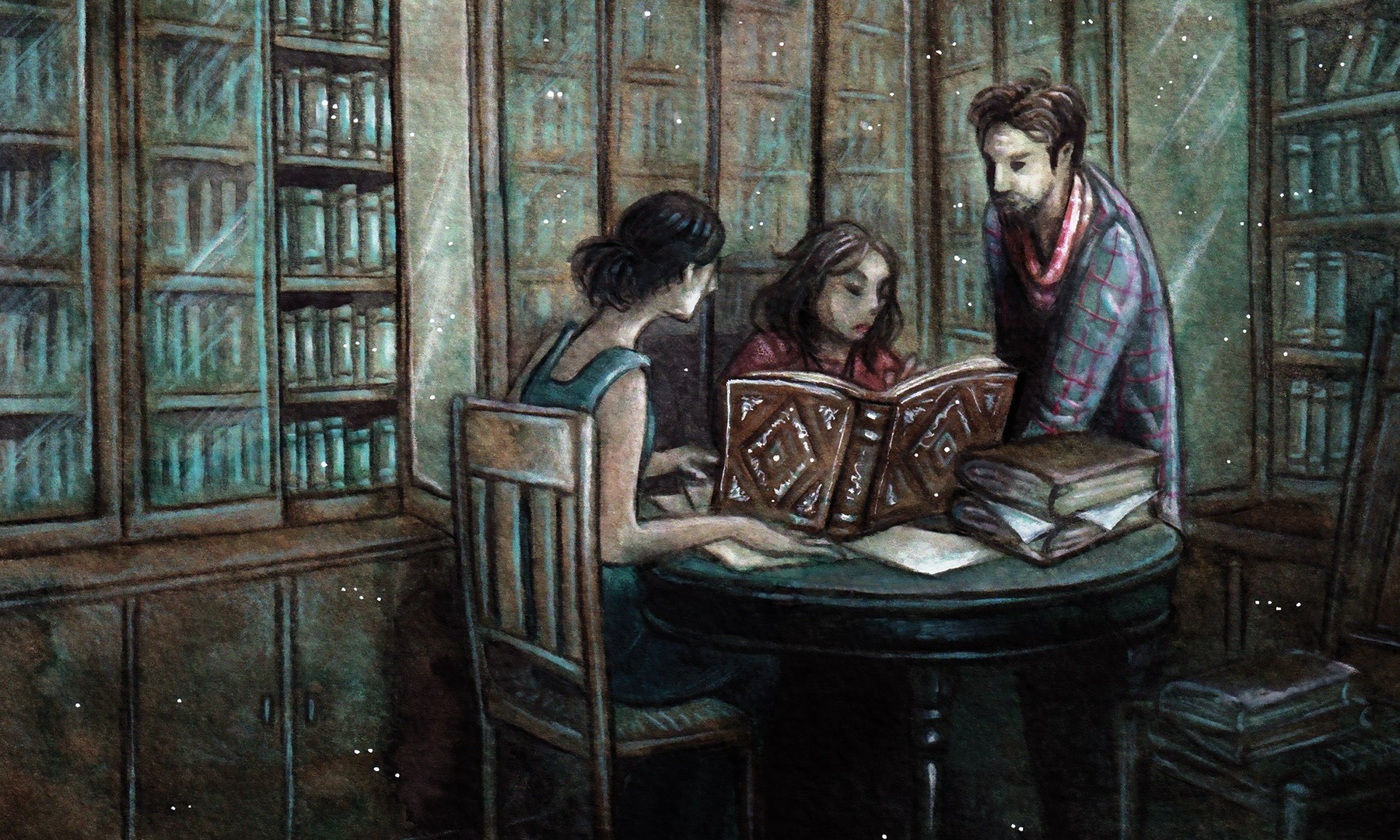

We’re pleased to present our next excerpt from The Chromatic Court – an exclusive look at Jon Black’s “The Green Muse.”

Featuring an exclusive look at Johannes Chazot’s illustration!

EBOOK

18THWALL | AMAZON US | AMAZON UK

“You know about the deaths?” Louis Vauxcelles asked with incongruous glee.

Squirming in his chair, Drieu Gaudin replied: “In Montmartre? The artists?” Since Drieu arrived in Paris six months ago and landed his job at Gil Blas, the literary newspaper’s editor had displayed no interest in him. Until today, when Vauxcelles summoned Drieu into his opulently apportioned office.

Vauxcelles nodded. “Five painters dead in as many weeks. Notice I say painters, not artists,” he sniffed. “Even for Montmartre, we’re talking about the very worst. Cubists,” the editor did not so much speak that word as seethe it. “People are whispering ‘murder.’ The gendarmes aren’t talking. But rumors and the scandal sheets hint at outrageous things.

“We have an opportunity here. We’ve been forced to accept the artistic conceits of the impressionists and post-impressionists, acknowledging some of them were not talentless. Then came the indignities of the Fauves, with their childish paintings and wild colors and forms. But never has there been anything like the Cubists. They deliberately mock beauty and tradition. I believe Cubism intends to destroy art itself.”

Vauxcelles paused. “I’ve looked through your articles, especially your art reviews. May I advance a guess that you studied painting before coming to Paris from…wherever you’re from?”

“Aquitaine, yes. I studied at the École Beaux Arts in Pau and…” Drieu intended to add he still painted but Vauxcelles cut him off.

“I don’t need details. I just need to know you’re the one I want.”

“What, exactly, do you want?” Drieu asked.

“For you to get inside the Montmartre set. I can’t use my other art writers. They’d be recognized. But you’re new. You’re unknown. Once you’re in, learn what you can about the deaths and write about it. A rash of dead Cubists? You know there’s scandal behind it. But, if you need, embellish your findings. I want something so depraved it will end Cubism for good. I’ll ensure your story gets onto the front page and that your future with Gil Blas is long and bright.

“I’m honored by the opportunity and your trust. But shouldn’t Cubism be fought on artistic grounds rather than scandal surrounding dead artists? It doesn’t seem right.”

“The Cubists and all the small-mindedness and aesthetic brutality masquerading under the label ‘avant-garde’ don’t play by gentlemen’s rules. We can’t afford to, either.”

“I’m not a crime reporter. Death and tragedy, they make me uncomfortable. So ghoulish.”

“Let me be clear, this is not a request. Do it. Or you’re out. You’re a promising young writer. But Paris has a dozen promising young writers waiting to take your place. This city swallows people like they’d never been born,” Vauxcelles’ smile could be mistaken for sympathy.

Drieu knew he’d been fortunate to land this position so quickly. At Gil Blas, Paris’ top cultural journal, he wrote about art, literature, theatre, and other haute themes without the pedestrian stories with which most novice journalists had to content themselves. “Very well, how do I start?”

“Begin with the newspapers and scandal sheets. Familiarize yourself with the facts. When you’re done, I’ve got someone to you lead into Montmartre itself.”

Departing the office, Drieu took a moment to chat with Barbette, Vauxcelles’ personal assistant. As she could afford a Paul Poiret dress to wear to work, he suspected she provided him other services as well. Drieu did not let that preclude some good natured flirting. Putting down the latest issue La Figaro, filled with coverage of the tragic fate of White Star’s “unsinkable” liner, Barbette batted her eyelashes and responded in kind.

That evening, back at the 11th Arrondissement hôtel he’d occupied since coming to Paris, Drieu cleared away the remains of the chicken broth and vegetables potage he’d made. After meeting with Vauxcelles, he’d treated himself; adding some wild mushrooms bought from the country woman near his omnibus stop. He corked his leftover vin rouge and carefully wrapped the remaining half-baguette, setting them aside for breakfast.

After pressing his other suit, Drieu reposed at his desk. Its mottled patches of vanished lacquer exposed the bare wood underneath. Staring at his secondhand Écrie Royal typewriter and desiring to write, only restlessness came to him. Moving to a threadbare chair, he attempted to read Le Monde and the provincial papers his mother posted from Bordeaux. Still, restless returned.

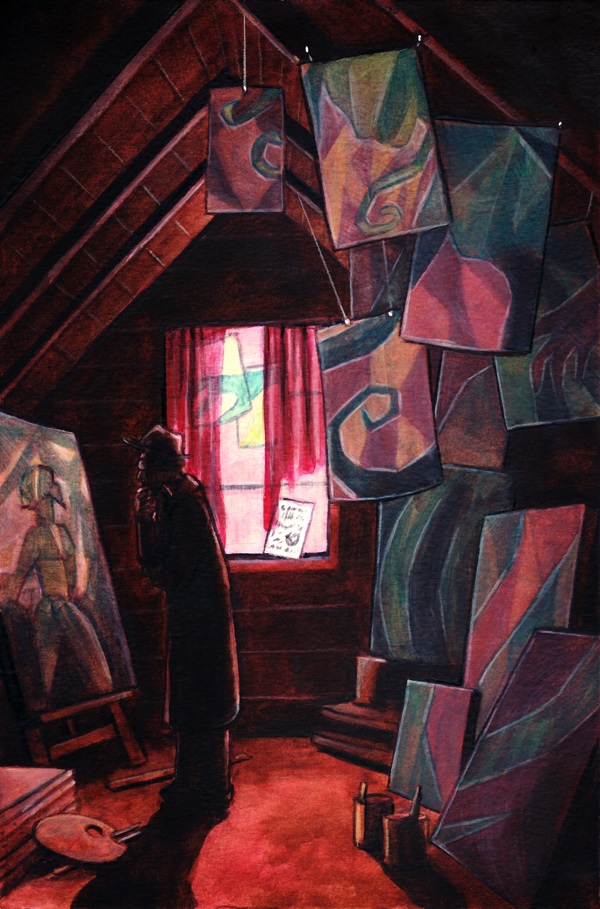

Finally, from his desk’s bottom drawer, Drieu removed the sketch. Using colored pencils, he’d made it at a gallery showing. Drieu carried it to his easel, which faced the wall in case polite company came. Rotating the easel toward him, he resumed painting his half-finished copy of Vlaminck’s Potato Pickers recreated from the sketch. Drieu secretly admired, even envied, the Fauves’ use of vivid colors to hint at that which could not be rendered directly.

Mixing viridian green on his pallet, he fleshed out the vibrant foliage which tied together Potato Pickers’ impossibly blue sky with the riotous orange and reds of its fields. Drieu knew many people, including his editor, would not approve.

Drieu reached Gil Blas early next morning. Like any good paper, it kept an eye on the competition by subscribing to most of Paris’s 80 newspapers: the conservative La Figaro, the socialist La Monde, the ponderous Le Temps, the trite Le Petit Journal, the fanatically religious and anti-Dreyfusard Le Croix, and even Excelsior, Gil Blas’ only rival as a cultural daily.

The periodicals painted a broad outline. Five deceased artists: Karl Schroeder, a recent arrival from Zurich’s coffeehouses. A brace of locals, Zacharie Jacquier and Antonin Basnard. Rudolpho Odelion from Cuernavaca, Mexico, had been a sculptor dabbling in painting. And, most recently, Valentin Accambray, a Creole from La Reunion called “Le Canari,” both for his sunflower yellow hair and propensity for gossip.

Four were found in their studios. Even the authorities and respectable press acknowledged that three of them qualified as “locked room” mysteries that would interest Arsène Lupin, or his stodgier counterpart in Baker Street across the Channel. But they remained curiously reticent about the causes of death.

What Drieu needed next could not be had within the offices of a respectable periodical like Gil Blas. On the streets, he made his way from newsstand to newsstand snapping up issues of Paris’s scandal sheets. These publications, typically printed on low-quality paper, prized graphic photos and lurid prose over typesetting, proofing, and truthfulness.

The scandal sheets suggested that the legitimate press barely scratched the surface of the outré elements in the artists’ demise. Their cause of death remained undetermined. But the options were bizarre.

It could be the foul, mucus-like substance found on each body. Some victims were merely splattered, others had been drenched. The ichor was described variously as blue-green or blue-gray. The gendarmerie suspected some kind of poison. Toxicology reports proved inconclusive.

Or it might be the punctures. Tightly grouped wounds the size of fingers, as if the victims had been stabbed repeatedly by a rapier, ice pick, or some great insect’s proboscis. Yet the wounds often missed the vitals.

The scandal sheets provided curious revelations about two victims. Le Canari was found outside, far from his studio. Face down, his arms and legs were splayed as if sprinting. The mysterious blue-gray sputum stained his yellow hair.

Odelion, the sculptor, had mixed all the sculpting plaster in his studio and, when he died, was frantically applying it where his walls met ceiling and floor as well as to the door jambs and window sills. Dried plaster covered his hands and clotted his hair. It was believed the sculptor had kept a dog. A glob of plaster on the floor preserved a large, canid paw print. Efforts were underway to locate the animal.

Scandal sheets and legitimate papers alike noted “expressions of fright” etched on the dead men’s faces.