Forgive the dust. We’re still in the final stages of re-designing the website. But we couldn’t wait to share John’s exploration of the Flying Dutchmen a moment longer. Normal service resumes next week.

John Linwood Grant

If I seem dry sometimes in my meanderings through classic tales, then perhaps I can ease the desiccation by pointing out that little relaxes your librarian more than reading Scrooge McDuck comics. Irascible, penny-pinching and self-centred, yet with traces of care and conscience occasionally peeking through, this Scrooge is an absolute treat.

Carl Barks (1901 – 2000) was the famous Donald Duck artist, creator of Duckburg and of Scrooge McDuck, and he was surprisingly influential. In fact, if you like Raiders of the Lost Ark, you should know that the great boulder which rolls after Indiana Jones at the start was based on the Carl Barks 1954 Uncle Scrooge adventure The Seven Cities of Cibola.

In 1959 Barks wrote and drew the magnificent Flying Dutchman adventure of Uncle Scrooge, Donald and his nephews – a masterpiece in supernatural literature (if you like ducks). It’s a great story, and inevitably leads me to mention the origins of the Dutchman legend. It’s possible that nowadays most people will connect it with the Pirates of the Caribbean films, but it goes way back, probably to the 1600s.

Over four centuries, the Flying Dutchman has mutated many times. Usually the Dutchman is the ship itself; sometimes the Dutchman is its captain, cursed to be the equivalent of the Wandering Jew. The story was certainly established by the middle of the 18th century, and there are two named candidates its origin: a Dutch explorer called Van der Decken and a man called Barend or Bernard Fokke. Both were sea-captains who were supposed to have worked for the Dutch East India Company, and made extensive voyages around 1650 – 1680.

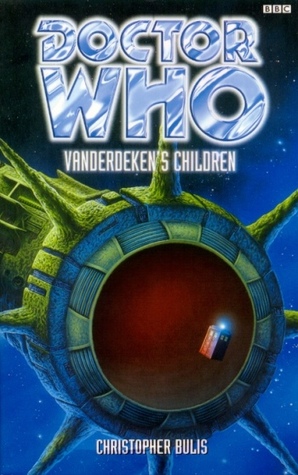

Not a lot is known of Captain Van Der Decken, AKA Cornelius Vanderdecken. The tale is that his ship got caught up in a storm around the Cape of Good Hope (South Africa), and he swore that he would finish the voyage even if it took him until Judgement Day. It was said that because of the vow that he was forced to sail the seas forever by the Devil. His name has been utilised many times since, with various spellings. For example, in the Doctor Who novel Vanderdeken’s Children (1998), by Christopher Bulis, the Doctor (the Paul McGann one) describes the crew of a ghost ship as the metaphorical descendants of The Flying Dutchman.

Captain Barend Fokke was certainly genuine. A Frisian born sailor, he was renowned for fast voyages between Java and Holland (then the Dutch Republic). In 1678 he is supposed to have covered the distance in just over 3 months. This was pretty impressive, and gave rise to talk that he was in league with dark powers, possibly the Devil himself.

The typical scenario for oral tales and books was that a doomed captain/ship and crew would appear to other ships, either dark and ruined or haloed with a ghostly light, and often during a storm. Sometimes the sight presaged evil to come, sometimes it was just one of those things put there to remind you that you needed to go to confession again fairly soon.

The long literary trail starts in the 1790s, and is a bit too convoluted to cover properly here. To give you the flavour of the early stories, here’s a contemporary account. This was written by George Barrington in his book A Voyage to Botany Bay (1795). Barrington was a transported pickpocket, and it seems likely that whatever he produced was re-written for publication, but the key passage goes:

I had often heard of the superstition of sailors respecting apparitions and doom, but had never given much credit to the report; it seems that some years since a Dutch man-of-war was lost off the Cape of Good Hope, and every soul on board perished; her consort weathered the gale, and arrived soon after at the Cape. Having refitted, and returning to Europe, they were assailed by a violent tempest nearly in the same latitude. In the night watch some of the people saw, or imagined they saw, a vessel standing for them under a press of sail, as though she would run them down: one in particular affirmed it was the ship that had foundered in the former gale, and that it must certainly be her, or the apparition of her; but on its clearing up, the object, a dark thick cloud, disappeared.

“Nothing could do away the idea of this phenomenon on the minds of the sailors; and, on their relating the circumstances when they arrived in port, the story spread like wild-fire, and the supposed phantom was called the Flying Dutchman. From the Dutch the English seamen got the infatuation, and there are very few Indiamen, but what has some one on board, who pretends to have seen the apparition.

And in 1821, Blackwood’s magazine published an anonymous Flying Dutchman tale called “Vanderdecken’s Message Home; or, the Tenacity of Natural Affection,” which included the belief that crew of the Dutchmen would seek to send letters to loved ones, even though the recipients would be long dead.

Soon a vivid flash of lightning shewed the waves tumbling around us, and in the distance, the Flying Dutchman scudding furiously before the wind, under a press of canvas…. One of the men cried aloud, “There she goes, top-gallants and all.”

If you want to track the legend as it developed, it’s easy to do. Edgar Allen Poe’s MS. Found in a Bottle (1833) includes this description:

At a terrific height directly above us, and upon the very verge of the precipitous descent, hovered a gigantic ship of nearly four thousand tons. Although upreared upon the summit of a wave of more than a hundred times her own altitude, her apparent size still exceeded that of any ship of the line or East Indiaman in existence.

Her huge hull was of a deep dingy black, unrelieved by any of the customary carvings of a ship. A single row of brass cannon protruded from her open ports, and dashed off from their polished surfaces the fires of innumerable battle-lanterns, which swung to and fro about her rigging. But what mainly inspired us with horror and astonishment, was that she bore up under a press of sail in the very teeth of that supernatural sea, and of that ungovernable hurricane.

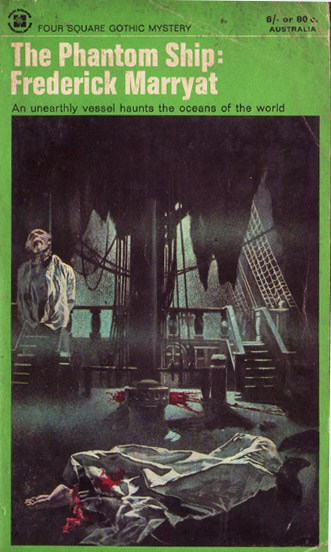

Frederick Marryat’s book The Phantom Ship (1839) is basically about the Flying Dutchman legend. Philip Vanderdecken (remember that surname?) seeks to save his father, who has been doomed to sail for eternity as the Captain of the Bewitched Phantom Ship, after he made a rash oath to Heaven and slew one of the crew whilst attempting to sail round the Cape of Good Hope. Vanderdecken discovers that there is a way by which his father may be laid to rest, and vows to live at sea until he has achieved this. In the decades that followed, Washington Irving and Henrik Ibsen mentioned the Dutchman, and the motif has continued to this day.

For science fiction fans, Roger Zelazny’s neat short story “And Only I Am Escaped To Tell Thee” (1983) tells of a sailor who escapes from the Flying Dutchman and is rescued by sailors who welcome him to the Mary Celeste. In Frank Herbert’s Dune, Lady Jessica talks of the Ampoliros, a legendary ‘Flying Dutchman’ of space. “Like the men of the lost star-searcher, Ampoliros – sick at their guns – forever seeking, forever prepared and forever unready.” In fantasy, Brian Jacques wrote a trilogy of fantasy/young adult novels concerning two reluctant members of the Dutchman’s crew, a young boy and his dog (beginning with Castaways of the Flying Dutchman [2001]).

There are many more. Whether it be through enjoying Scrooge McDuck, ploughing through the sometimes tedious The Phantom Ship of Marryat’s, or watching Bill Nighy’s squirming face tentacles in the film Deadman’s Chest, the legend maintains its hold…

Clayton Howard

Amazing article! Outstanding!

D. Kaufen

Excellent story it is, surely. We have been waiting for this.

Mac

Way cool! Some very valid points! I appreciate you writing this write-up, plus the rest of the website is really good.

Van

I want to suggest you some fascinating topics. I would love to read more about other European folklore and how it appeared in science fiction//where it comes from. Maybe you can write your next articles relating to this article. I desire to learn more about it!