Just Like in the Movies: Ruth Rose (#2): It’s Not a Lost Film; It’s Just that Nobody’s Looking.

Micah S. Harris

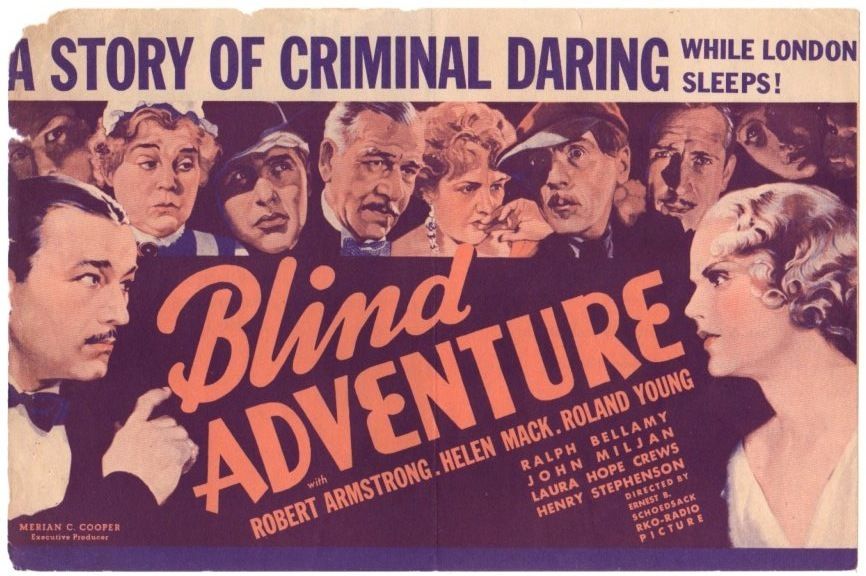

I Guess that’s Why They Call It Blind Adventure

We last left Ruth Rose, if not atop the Empire State Building with King Kong, still at an enviable pinnacle: that of her screenwriting Hollywood career. With her first script outing, she co-authored a verified classic of world cinema. As with the rest of the fabulously creative principals involved with the lightening-in-a-bottle phenomenon that was Kong, nothing else she ever did would have as near an impact.

Having only one way to go from this point, however, was not nearly as traumatic a trend for her as it was for Kong. Although always a creative person, she had apparently had no particular aspirations to ever be a screenwriter. Kong creator Merian C. Cooper had pulled her in from left field with hopes she might put the too-long-in-progress King Kong script in shape.

Before she ever put pencil to paper (her preferred method) to write the first word of her first screenplay, Ruth Rose already had had careers as both an actress and an explorer. While having made a tentative step into prose fiction with a single short story sale and written non-fiction accounts of her adventures, she seemed more or less to have been a dabbler at writing.

Nevertheless, she had co-written one of R.K.O.’s hits of 1933. Not the biggest that year for the studio, but it was Depression-era plenty (“No money! Yet New York (City) dug up $89,931 in four days to see King Kong!” exclaimed the R.K.O. memo to exhibitors). Cooper immediately brought her back when a sequel was approved. This time, there would be no need for a succession of script writers struggling to achieve a narrative to sustain his vision. Rose was a rose was a rose…and Cooper knew it.

Son of Kong (1933) has long stood diminished in more ways than one beside its grand sire. But even “little” Kiko gets out of his dad’s shadow to see the sun shine more than the contemporaneously filmed other King Kong follow-up. This overlooked film involved some of the same key participants of both Kong and Son, including scriptwriter Ruth Rose.

So, we’ll pick up with the goings-on on Skull Island post the departure of its King when our column returns in April. This month, we’ll focus on 1933’s unjustly neglected Blind Adventure, also from R.K.O.

Information on Blind Adventure is less than forthcoming. One suspects just one brief stop-motion scene by Willis O’Brien, less than thirty seconds long and not even involving a giant spider, would have been all it took to change all that. Out of my roughly baker’s dozen of books related to King Kong and its creators, only those ever-vigilant custodians of Hollywood obscurities, Michael H. Price and the late George Turner (the Forgotten Horrors series), mention it to any extent in Spawn of Skull Island (a revised edition in collaboration with Turner’s son Douglas of the 70s’ classic The Making of King Kong by Turner and Orville Goldner).

I would love to know when, why, and how Blind Adventure was conceived, beginning with whose idea it was to start with. It might be the only thing filmed that Ruth Rose wrote that was completely her (everything else was collaborative to some degree). It’s certainly the most different project she and her husband, director Ernest B. Schoedsack ever did (either together or separately).

Son of Kong and Blind Adventure reveal that Rose, left to her own devices either by necessity (as in the case of Son of Kong) or desire, worked best on a smaller canvas than her frequent collaborator Cooper preferred. Though both stories are adventure films, they are as much character as action stories. Further, these movies’ characters, while definitely movie characters, are not the romanticized, larger than life ones of Kong.

Rose’s conceptions of a hero or heroine are comparatively low key and relatable, tending to act out of necessity and just trying to get through it all. Left alone with her pencil and pad, she excels at developing protagonists fitted to more budgetary confined backdrops, characters that lack the more archetypal dimensions those of Kong took on from the contributions of her collaborators.

These two Kong follow-ups are also probably the most autobiographical Ruth Rose ever got in her screen work. Each movie seems rooted in some aspect of her life “so far” (that is, the early ‘30s, and her initial Hollywood career). Son of Kong, of course, reflects her exploration phase, but Blind Adventure her earlier, theatrical period.

Blind Adventure, in fact, feels largely rather like a play. Recall that Rose’s father was a noted playwright (though not always noted well – he was reportedly pretty much despised as a hack by authors who saw him adapt their works for the stage), and she, at a young age, had been an actress. From Broadway, I believe came her own aesthetic sense of story and dialogue.

Ah…the dialogue. There are lines that make you wish Rose had had the opportunity and inclination to really focus on producing some books for the Great White Way or even a Thin Man style movie series with a husband and wife detective team. Rose gives our leads, Robert Bruce (Robert Armstrong) and Rose Thorne (Helen Mack), who have far superior chemistry here than in Son of Kong, by the way, some fun banter:

Rose: Who’s that?

Robert: The dead man.

Rose: He’s not dead.

Robert: You’re telling me.

Or,

Robert: Where’s the roof?

Rose: Upstairs, I imagine.

Or,

Rose: If only we had your overcoat…..

Robert: And if we had some ham, we’d have ham and eggs – if we had some eggs.

Rose Thorne’s character is established from her entrance. Just back from the theater, she encounters two men she has never seen before in her uncle’s living room.

Rose’s Uncle: We’ve just met these two men under strange circumstances.

Rose: How jolly! May I do it too, or are the strange circumstances over?

In actress Helen Mack, particularly her role as Rose Thorne in Blind Adventure, I believe we have the best example of “the Ruth Rose heroine.” It is worth remarking that she is the only one of her ingenues who shares her creator’s name. We may well wonder if “Rose Thorne” is Ruth Rose’s “identification character,” both biographical and glamorized.

In contrast to Kong’s fairy tale damsel in distress Ann Darrow, a character Rose helped define but whose screen realization made Darrow more identifiable with Fay Wray’s off screen persona than Rose’s, “Rose Thorne” is an ingenue in the original sense of an ingenious (that is, clever) young woman.*

Indeed, once pulled into the dangerous proceedings, Rose Thorne proves to be the best girlfriend a guy over his head in peril could hope to have at his side. She is sweet, sharp, and perky fun in her feminine formal gown, but, far from being preoccupied with breaking a nail or getting her hair caught in the wind, she proves to be naturally plucky, quick, smart, faithful, and brave. I am describing Rose Thorne here, but I suspect that much of that previous sentence is also a pretty accurate description of Ruth Rose.

Blind Adventure’s narrative is especially notable because Rose’s screenplay seems to be a self-conscious inverse of the typical Cooper-Schoedsack production. I wonder if she was having some fun with her best fellows – and herself. Armstrong, whose signature character is Carl Denham, here plays an adventurer who, like Denham (and Cooper and Schoedsack), made his money out in the wilds.

The twist is that our hero isn’t ever truly in peril until he finds himself out of his out-of-doors element in the urban environs of London. Bruce’s dialogue establishes early on that the city is where his daydreams have taken him, and it’s there, not the Yucatan or Skull Island, that he has come for a larger-than-life experience. Instead of wide open spaces, Rose’s inversion of the Cooper-Schoedsack template places most of Blind Adventure’s action indoors.

There are elements of comedy in other Rose screenplays, but comedy is central to the frothy concoction that is Blind Adventure. My favorite is an example of George Bernard Shaw’s observation that America and England are two countries divided by a common language.

When Robert and Rose crash a society party with the intent of just passing through as a means of escape, an aging dowager pins them down and goes on about her long lost glory days as a belle of the ball.

Then, she casually announces to Bruce, “Young man, I’d think I’d like a bit of trifle.”

This has previously been established as a British party confection, but the American Robert mistakes her word choice to mean this elderly stranger is flirtingly inviting his playful physical advances.

“I beg your pardon?” he asks.

“I fancy a bit of trifle,” she reiterates.

Watching this scene play out cracked me up. I must say, seeing Ernest Schoedsack, a director associated with the outre, spectacular action sequences, and exotic documentaries, successfully pulling off drawing room screwball comedy is a one-of-a-kind treat.

Blind Adventure is a fun little romp and a fascinating sidelight into what some of the key creators of King Kong could do without a jungle, dinosaurs, or any sacrificial maidens available.

In a world where the 1933 Mystery of the Wax Museum can play as a special feature on the DVD of its remake House of Wax, and the obscure drive-in monster classic Equinox can get the extra of the creators’ even more obscure home movie (Zorgon: the H-Bomb Beast From Hell) on its Criterion release (!), Blind Adventure at least deserves special feature status on a new Blu-ray release of Son of Kong.

Give Blind Adventure its own commentary or throw in a mini-documentary and the results could be, well, eye-opening.

Next time, it’s part three of Ruth Rose and that other follow-up to King Kong she wrote in 1933….

*While many assume Ann Darrow is Ruth Rose’s onscreen equivalent, George Turner reported that Rose said the association came as a surprise to her. Rose Thorne and the other Helen Mack characters more closely reflect Rose in real life as either an ingenious adventurer or onstage ingenue. Rose herself seemed to associate the real Fay Wray’s offscreen “class and delicacy” (her words) as synonymous with the actresses’ on-screen character of Ann Darrow.

Hear Ruth Rose and Ernest Schoedsack SPEAK on this priceless artefact from the George E. Turner archives!

Dylana Gilliam

I’ve seen most of Ernest Shoedsack’s films but haven’t ever been able to find Blind Adventure. If you have any info I’d definitely appreciate on how to watch it