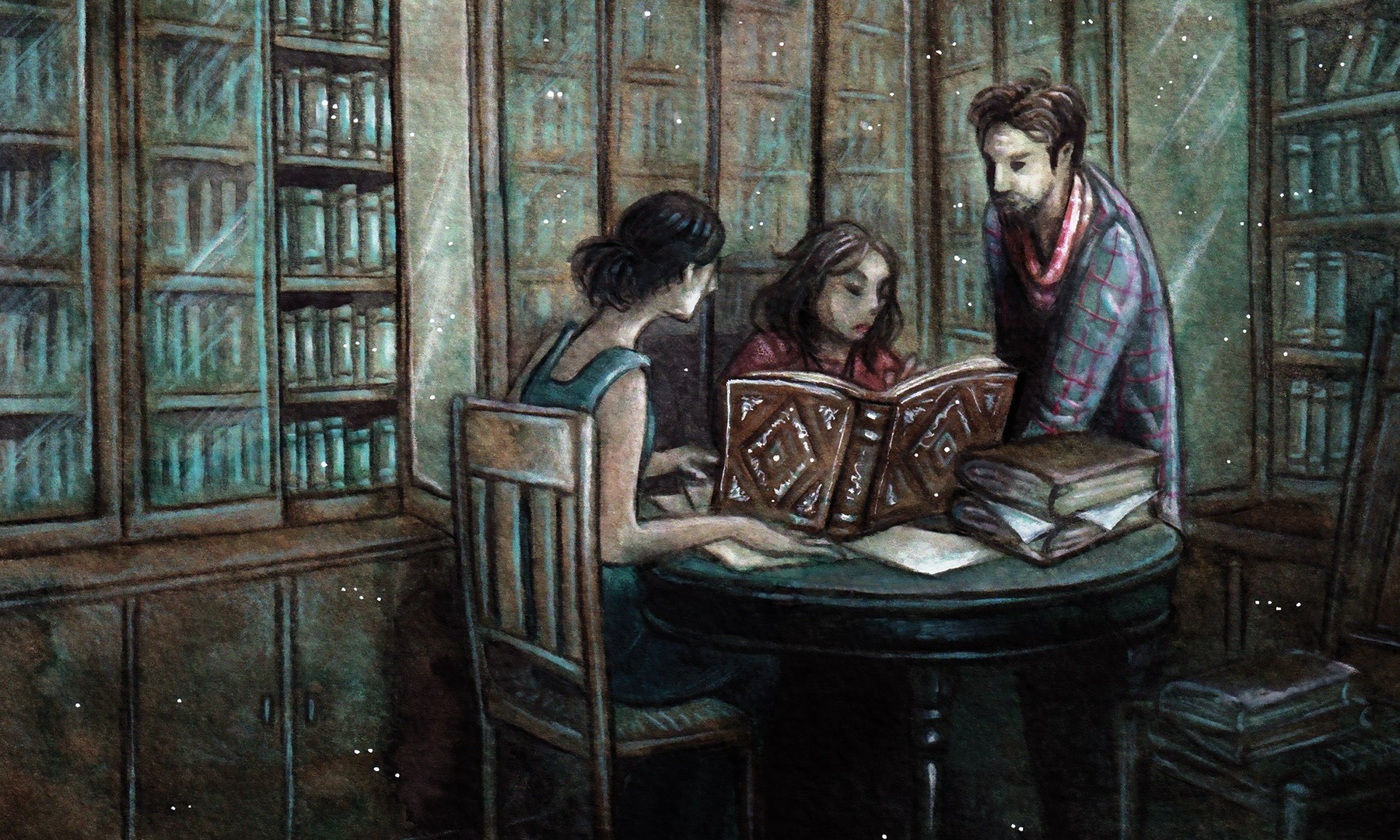

John Linwood Grant’s “Death Among the Marigolds” (from Silver Screen Sleuths!)

We’re pleased to present our another excerpt from Silver Screen Sleuths, an exclusive look at John Linwood Grant’s “Death Among the Marigolds.”

EBOOK

18THWALL | AMAZON US | AMAZON UK

Margaret Rutherford tangles with ghosts and Nazis at a stately manor home where all may not be as it seems.

London, September 1941

There were two explosions near the Piccadilly Theatre on that warm September evening.

The first one was caused by a homeward bound Heinkel, shedding the last of its load. It was a token effort only, for the Blitz itself was over. Proving that God loved a show, the bomb missed the actual theatre. Unfortunately the building had already been weakened by a raid some time before. The management decided to have the damage surveyed, and gave strong indications that further performances would have to wait.

The director was furious—his ‘Blithe Spirit’ was capturing the capital. The cast, on the other hand, were grateful for even a day or two off. Plans were made to see families, to drive out of the city for a relaxed break, and in general to take their feet off the boards.

The second explosion was less usual, and quite localised. As the actors sorted out their belongings and considered this unexpected freedom, the stage door was the scene of a much smaller blast.

“But I have to! I have to see her!”

The speaker was a mass of wild blonde hair and smudged make-up, barely over five foot tall and dressed in a black velvet cape which would have suited any revival of an old romance. The doorman, who looked like a doorman, was being slowly beaten back into the Piccadilly. He held out his large hands to ward off small fists until relief arrived.

“I told you, miss, you can’t go in the—”

“Is there a problem, George?”

He turned, managing a grateful smile. “Miss Rutherford, it’s this ’ere girl. Insists she sees you.”

“I’m not a girl,” said his assailant. “I’m Lily Maunsey, and I really, really, need to talk to Miss Rutherford. Really.”

The actress, whose own cape was of a more sensible tweed, stepped up to the firing line. “Now now, dear. Why don’t you come inside and tell me what the fuss is about? Yes, George, it’s all right.”

The theatre bar was still open. A reluctant barman found a brandy for the girl, and Margaret steered them both to a table, wiping away the fallen plaster with her sleeve.

“I’m an enormous, enormous admirer.” said Lily, large brown eyes fixed on the actress’s face. “I saw you in Hull, and Leeds, and Manchester, and I’ve been to absolutely loads of performances of Blithe Spirit, and you were wonderful in Rebecca, far better than that Judith Anderson, and I saw you in—”

Margaret held up one hand. “That is most gratifying, dear. But the fuss at the door…”

“I’m in awful trouble, Miss Rutherford.”

The older woman’s somewhat crumpled face crumpled more in concern.

“Goodness. Why on earth is that?”

The girl leaned forward.

“There are dreadful things happening at home.” She sat back again. “And you are the only one I can trust.”

It took two brandies for the girl to deliver the story. Lily, only surviving child of Sir Cedric Maunsey, eighth Baronet of Kelwich, was rather emotional.

“Miss Rutherford, it’s my older sister, Alice—she’s trying to talk to me about some awful problem, but she won’t make things clear.”

“Is it a very personal matter perhaps? Family can be difficult. Or is she unwell?”

Lily blinked at her half-empty glass. “Oh, nothing like that. She’s dead”

“Good heavens!”

“I mean, she died a couple of months ago, but I can sense her. Like you do in Blithe Spirit, you see?”

“My dear, I—”

“I’m sure our house is doomed, or cursed, or that sort of thing. Alice is—I don’t know—hovering over me, trying to break through.” The girl was not to be halted. “Daddy’s useless, and since most of the staff joined up to fight, the place is falling to pieces, and I really, really don’t have anyone to talk to apart from nanny, who’s lost most of her marbles anyway…and we can’t even get decent butter any more.”

Lily drew in a deep breath, and stared expectantly at the actress, who was as bereft of words as the girl seemed full of them. Margaret felt much as she did when presented with a script for the first time. The words were there, but not the meaning.

Lily took advantage of the pause.

“I’ve seen Spring Meeting three times. You were so wonderful in that film! I’m staying with my aunt in Pimlico this weekend, but she’s an old biddy and half-deaf, and absolutely no one listens to me, and I have to go back home. My sister is trying to warn me of something terrible, but I don’t know what it could be. Please, please help me!”

It was Margaret’s nature to be attracted to waifs and strays, but this situation seemed beyond common sense. She knew nothing of troublesome sisters, dead or otherwise.

“It sounds most distressing, but I’m not sure how I could help.”

The girl sat up straight. “You are Madame Arcati.”

“But that’s merely a part I play, dear.”

“Oh, I do know that, but you believe—I can see it when you’re on stage. I’ve read about you. I’ve read everything about you, Miss Rutherford. You’re sensitive to these things. You’re kind, and decent, and you’re so determined, and I’m very confused…”

If the tear in the girl’s eye was theatrical, it was very convincing. Margaret softened.

“What did you want me to do?”

“Come home with me, just for a day or so?”

“I don’t think I could possibly—”

“I know, I just know that you won’t let me down.” One tear became two, accompanied by a wild stare. “Would you rather I turned to strangers?”

The actress was about to point out that she was a stranger, but hesitated. The girl’s huge eyes, set above a small nose and a determinedly-pointed chin, were awash with genuine distress—and a certain blind faith.

It seemed that somewhere between a first and second act, on one stage or another, Lily had decided that Margaret Rutherford was to be her saviour.

“Please, darling Miss Rutherford.”

Margaret was a poor liar, and when pressed, she admitted that she could, technically, come away for a short time. One by one her arguments were beaten down. Nor did it escape her that here was a young woman in need, at the only point in a long run when the theatre would not be requiring its actors.

Some bombs fell on one by chance; others, perhaps, had a purpose.